Hill giants, called haugjotunen in their own language,[12] were voracious, primitive giants defined by their gluttony.[7][13] They were the least of the commonly recognized "true giants", the shortest in stature, weakest in mind, and lowest in rank according to the Ordning.[7][14] Granted domain over the rolling hills by Annam All-Father millennia ago,[15][16] they were masters of its slopes and deeply connected to the land itself.[16][17][18]

Description[]

Hill giants normally stood around 16 feet (4.9 meters) tall,[5][11] but males could reach about 17 feet (5.2 meters) in height,[11] although some reports of giants from other worlds put them at around 10 to 10.5 feet (3 to 3.2 meters).[4][6] Females tended to be a bit shorter, at 15 feet and 5 inches to 16 feet and 4 inches (4.7 to 4.98 meters).[11] Their reported weight was around 4,500 pounds (2,000 kilograms),[5] but morbidly obese (and immobile) individuals were known to weigh over 10 tons (9,100 kilograms).[19][note 1] Their skin was a deep, ruddy brown, but they could also be light tan in coloration as a result of a life spent under the sun.[1][4][5] Their hair ranged from brown to black, and their eyes shared that color in addition to having red rims.[4][6]

Hill giants were basically humanoid in shape, but had an oddly simian in appearance, with low foreheads, stooped shoulders, thick limbs, and elongated arms shared by both genders. Despite being the shortest of giants, they had larger and more muscular appendages than other giant breeds. They had a rugged, barbaric look,[4][5] and if not for the lack of two heads could be mistaken for the relatively uncivilized ettins at a glance.[20]

The traits that other races often saw as attractive were known to be considered strange and worthy of scorn to hill giants. Straight teeth, neat hair, unblemished skin, clear speech, and a lack of drool when eating were abnormal, if not repulsive traits.[21] Their own sweat mixed with the reeking stench of the crude, rough animal hides they wore. Animal skins worn by hill giants were poorly stitched with hair and leather thongs, not stripped of fur, and rarely cleaned or repaired, since hill giants normally opted to simply add more skins on.[1][4][5][6]

Personality[]

A hill giant stealing pickles.

Hill giants were selfish and brutish bullies that often forced weaker creatures to do their bidding. They lived as uncivilized savages, surviving by foraging, hunting, and raiding for food when not coercing other, smaller beings into doing the work and feeding them.[1][3][4][5][18]

Although prone to evil behaviors, a hill giant's acts of cruelty were normally more along the lines of angry reactions than deliberate decisions. They were short-tempered creatures[22] whose form of chaotic evil was known to be defined by violent mood swings and losses of patience.[23] They were likely to go on a violent rampage if they felt deceived, mocked, or otherwise humiliated, and in their tantrums would rage against the guilty and innocent alike until they calmed down, grew hungry, or were otherwise distracted.[1] Their memories were also normally too short to hold grudges,[22] with some reported to forget those they recently met after waking up (which conversely could mean that any previously built rapport could be forgotten).[23]

However, while most hill giants (around 40-50%) conformed to the chaotic evil behavior commonly found among them, true neutral and even chaotic good hill giants were not totally unheard of.[4][24][25]

Intelligence[]

Hill giants equated size with strength, functioning based on a "bigger is better" mentality. Smaller creatures, sentient or not, were prey to hunt with impunity, while larger creatures, like dragons and bigger giants, were dangerous adversaries.[1] Following this logic, a hill giant of average intelligence might think to consume food in attempt to grow immense (not understanding biological limitations) and therefore superior.[26][27] The idea that giants were stupid was perhaps the most commonly stated misconception surrounding them, but few kinds embodied the fallacious belief more than hill giants.[28]

Hill giants were reckless,[4] sluggish,[2] and notoriously moronic,[29] such that they would died out long ago if their great size and formidable power did not compensate for their dull wits and lazy disposition. Ironically, their mental weakness was partially perpetuated by their brute strength. Having never faced adversity that required adaptation and improvement, hill giants had managed to survive for millennia[1] with their lacking ambition,[7] living unchanged as barbarians with simple minds and underdeveloped emotions.[1]

The least intelligent hill giants were mentally closer to beasts than civilized beings, while the brightest were above average compared to most humanoids.[28] Hill giants were blunt and direct in conversation, and though reasoning with them was useless, they could be manipulated into taking certain actions by more clever creatures. They had little concept of deception, to the point where villagers standing on each other's shoulders could cover themselves in blankets and hold a large, circular object above themselves to fool a hill giant into fleeing from the opposing giant.[1]

Hill giants were much like ogres in terms of mental prowess, being as intelligent, if not stupider, than the smaller giant-kin.[28] Both had a tendency to be overly literal due to not thinking about their directions, misinterpreting even the simplest instructions due to their lacking consideration.[30] However, though potentially less intelligent than ogres, hill giants shared with them an exceptional cunning,[28] even outmatching them in craftiness.[18] Though they themselves were easily susceptible to the schemes of others, both were capable of surprising feats of cleverness, albeit in pursuit of limited desires.[28]

Abilities[]

As one would expect, hill giants were incredibly strong and extremely resilient.[4]

Combat[]

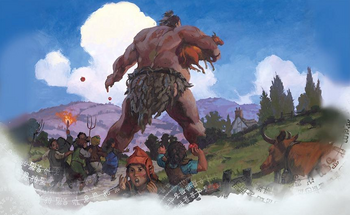

Hill giants on the offense.

Despite lacking brainpower and being infamously clumsy, hill giants were capable combatants.[5][29] Some of the already physically formidable beings even trained to become barbarians.[4] When they went looking for food, hill giants did so alone or with an animal companion, such as a dire wolf, to avoid having to split their spoils with other tribe mates.[1]

A hill giant's preferred combat strategy was to utilize the time-honored giant tactic of throwing rocks at their enemies.[31] They pelted their enemies with boulders from high, rocky outcroppings, allowing them to injure their foes while limiting the risk of personal injury.[4][5] Assuming they could not pull rocks from the bags most giants carried around,[31][4] they could simply pull rocks up from the ground.[1] Normally the boulders they used were around 3 feet (0.91 meters) in diameter and 325 pounds (147 kilograms) in weight.[32] Their reported maximum throwing ranges varied, with the longest claimed distance being 600 feet (180 meters). They could also catch similarly-sized rocks (and other proportionate missiles) with an approximate success rate of about three in ten.[5][6][32]

Once an opponent got into melee range, hill giants stopped hurling stones and began fighting in close quarters.[3] They favored the use of oversized clubs,[4][5][6] and could uproot trees to use as weapons if needed.[1] Some hill giant hunters were known to use javelins, but they still carried throwing rocks with them.[18]

Hill giants had various favorite melee tactics. They loved overrunning smaller enemies at the start of a battle, trampling them underfoot before standing fast and swinging with their clubs.[4] When faced with more than one target, they made sweeping motions in an attempt to knock their enemies to the ground.[3] Some liked to hurl their whole, considerable mass at smaller foes, crushing their opposition beneath their formidable bulk.[33]

Even hill giants, as dim-witted as they were, recognized that smaller foes would attack their lower body parts. As such, when they knew they were going to face human-sized enemies, they took certain precautions. They were known to peel thick strips of bark from trees and strap them to their legs as make-shift greaves, and to tie logs and stones to their belts so that foes trying to move under them would have to beware the dangling obstacles.[8] Hill giants were also wise enough to know that a hopeless situation was one to escape from, rather than continue fighting to the death.[3] When faced with the prospect of death, they might even fall into incoherent blubbering and sobbing.[34]

Society[]

Like other breeds, hill giants had developed their own value system over the millennia, and their unique culture was centered around one thing — food. According to the hill giant belief system, the one true meaning of life was to satisfy one's appetites, and over the years the dull creatures had managed to take this simple philosophy of hedonism to surprisingly deep extremes. Unusually learned hill giants were known to write elaborate poems using food and consumption in complex metaphors regarding the many trials of life.[29]

Given the hill giant tendency to put all sorts of repulsive and rotting things in their mouths with little hesitation, some theorized that the species had no sense of taste or were so hungry at all times that taste was irrelevant.[7] In truth, hill giants had, over the course of their long history, consumed almost anything one could imagine (including various sentient beings) and enjoyed almost everything they tried. The kind of food that humans and elves would find appealing were appallingly dull to hill giants, who preferred more exotic dishes,[29] and since most recovered from getting sick, they rarely learned to avoid anything.[7]

Despite their general ignorance and ineptitude, hill giants had unnatural gifts for both hunting and cooking,[29] and had actually developed some of the most sophisticated food preservation methods in all the Realms. Long had they known the benefits of smoking, salting, and freezing different foodstuffs, although despite these advancements about a fourth of their inventory was accidentally ruined or spoiled before it could be used.[36] They also had knowledge of certain properties of different foods, namely which were more fattening.[2]

Ordning[]

A hill giant's position in the Ordning (the social ranking system among giant breeds and giants as a whole) was based around an odd combination of physical might and gastral superiority.[37] Though the latter skill might seem like a strange factor to use for determining the chain of command, among hill giants, it was a trait synonymous with virtue. Because hill giants believed the purpose of life was self-gratification, it only made sense that the development of skills that helped them to accomplish that goal were the most worthy of being pursued, and thus that the giant who had best mastered such skills was obviously the most fit to lead.[38]

Size was the same thing as strength to hill giants, and consuming food was not only satisfying, but made them even bigger. As such, the tallest, widest, and heaviest member of a hill giant tribe (normally but not always still able to move) was considered the most successful and admirable.[1][7][19] On the other hand, the lazy creatures also realized that overexerting themselves often made them thinner;[2] as one might expect, girth was perhaps the one area where hill giants excelled compared to other giant breeds.[7]

The qualities that other beings expected or required of their leaders — including intelligence, decisiveness, and charisma — were not rewarded or recognized as important beyond their capacity to aid a giant in obtaining more food.[7] Some hill giants did not even consciously realize they followed an Ordning, simply operating on the belief that the larger and stronger giant was to be obeyed.[1] Only on rare occasions were relatively smart hill giants able to subvert their social order through cunning, such as by deceiving or intimidating others into giving them food or by gaining the favor of their superiors.[1][7]

For hill giants, Ordning challenges to rise in rank took the form of epic eating competitions where two opposing parties would devour huge piles of food. After the massive meals were prepared, (hill giants involved would try to obtain lots of their favorite foods for such battles) the contestants would emerge, consume, and return every three hours until one side couldn't continue. In "duels" between the most gluttonous (and likely among the highest ranking) hill giants, these competitions could go on for weeks, with neither side allowed sleep. Unbelievable portions were consumed by the end of such matches, which ended with both participants often feeling utterly sick and nearly immobile.[29]

At the top of a hill giant Ordning was the chief known as the storkokk, meaning "master eater" in their own giantish dialect. Because of the nature of the selection process they had to endure simply to obtain their positions in the first place, storkokks were almost always the most massive and rapacious hill giant in their steading. They also had among the greatest responsibility, for not only were they tasked with handling matters of state (which given hill giant attitudes would often sounded like discussions at an eatery), they were looked to by their kin for political leadership, spiritual guidance, and gastronomical inspiration.[39]

Below the master eater were the gluttons, the highest ranking of hill giants. They were tasked with supervising labor, law enforcement, and the creation of new rules, but their most important duties were, supervising the obtainment of foodstuffs, hunting, and the creation of new recipes. A glutton that failed in these duties (such as if their food stores gradually dwindled down to nothing) was severely dishonored, and the pressure to succeed was so dire for some that they resorted to dishonest methods (including stealing from other gluttons) to keep up appearances.[39]

The best and brightest hill giants were assigned the role of fetcher, a position meant to groom them for later greatness. Each was the assistant to a specific glutton and most master gluttons called upon their most trusted fetchers to handle minor details related to their positions, such as stocking the vegetables or non-exotic livestock. Hoarders meanwhile were those hill giants responsible for performing inventory, storing the perishables and cooking supplies, and reporting food levels to the relevant higher ups.[39]

A hill giant herdgorger's shepherd crook was useful for picking bits of wool out of their teeth.

Hill giant hunters stalked game and brought it back home (dead or alive), and were known to form hunting parties to do so. Certain limits, such as not hunting humans, were sometimes placed upon them depending on a tribe's diplomatic position. Conversely there were also gatherers, who obtained foods that could not be hunted or, ironically, gathered, by buying from merchants. Since hill giants had no use for treasure, they would often gladly pay above standard price for their purchases. Lowest in the Ordning were herders, who killed and butchered the tribal herd (or managed the slaves that did so) and were usually trained in various livestock fattening techniques (livestock sometimes including sentient humanoids).[39]

Social Structure[]

As with most giant breeds, hill giants were loosely organized into huslyder, a giantish word roughly meaning "families", that were responsible for taking care of children. For hill giants, huslyder were large and communal,[40] and could be relatively unregimented compared to other giant societies, even if each giant still had specific assigned roles.[39]

Normally a hill giant lair housed an extended family, sometimes including lone hill giants who were accepted into the family, which totaled around 9-16 hill giants. Of these, around half were male, a quarter female, and the remainder juveniles. Raiding and hunting parties of around 6-9 members were known to form, as were bands of similar numbers with the addition of 2-3 non-combatant members.[4][5]

On occasions where a hill giant of average human intelligence emerged, there was the capacity of hill giants to be rallied by the superior intellect, creating groups of hill giants anywhere from 2-4 times the ordinary number. Such self-titled "giant kings" often raided human towns, and might even go so far as to attack other bands of giants.[5] A hill giant tribe normally had about 21-30 members in addition to about 7-11 non-combatants.[4]

Among hill giants, the most maug (the equivalent of evil for giants) act a giant could commit was the betrayal of one's tribe. If a member of a tribe aided outsiders against that tribe, even for a morally good reason, all his peers, even those of good alignment themselves, would brand him as maug, and therefore worthy of shunning or punishment. On the other hand, even despicable hill giants could be convinced to stop a rampaging hill giant if he once betrayed his breed.[41]

Culture[]

On occasion, hill giants were known to amuse themselves with inane games, normally involving food or eating in some way. One such game, known as "stuff-stuff" had the hill giants see how many small creatures (such as halflings, gnomes, or goblins) that they could fit into their mouths and once without swallowing.[7] Hill giants were also known to take amusement from wading in pools of water (which doubled as drinking water sources), even in regions with extremely low temperatures, and sometimes created such pools by damming rivers.[42] The idea of wives and husbands was present among hill giants, although polyamory was noted to occur. Even if both subjects would miss each other if separated, daily spousal abuse was not unheard of.[27][43]

If a hill giant glutton discovered that his food stores were particularly well-stocked, they might decide to call a grand feast. A grand feast was a huge celebration infamous for total revelry and lack or restraint, and often ended with most of the tribe heavily drunk and fast asleep. During such feasts, an important guest from outside the tribe was often asked to part. This might be another giant chieftain or a diplomatic partner of another race, but since so few guests (including some higher-ranking giant breeds) could match a hill giant's sheer overindulgent gluttony, most would politely excuse themselves long before the end of the feast.[39]

In lieu of engaging in their own lacking and myopic culture, hill giants were known to ape the traditions of other creatures instead, copying their methods without proper consideration. For example, a tribe might copy elves only to topple forests trying to live in trees, while those that tried to take humanoid villages as their own often only got as far as the door before accidentally demolishing the walls and roof.[1] One such imitation took the form of a hill giant declaring itself king and demanding tribute of livestock and produce from nearby humanoids,[18] a tyrannical reign of terror defined by the giant's shifting mood, with the constant threat of it forgetting its own title and eating its subjects on a whim.[1]

Possessions[]

Like other giant races, hill giants kept their belongings on them by keeping them in huge, hide sacks.[5] The primary purpose of the bag, especially for hill giants, was to carry food, for being as large as they were, it would be unwise to travel without rations.[31] Usually it also contained a giant's personal wealth, as well as somewhere between 2-8 throwing rocks and 1-8 mundane items. Hill giant possessions were usually well-worn, filthy, reeking, crude, and often jury-rigged or salvaged from something else. Examples included a wooden bowl and spoon, a drinking cup made from a gourd or skull, or a hand chopper made from the broken-off head of a battleaxe.[4][5]

The crudely-sewn animal hides that hill giants wore functioned as leather armor. Nearly all hill giants wore such hides because they were a status symbol in some communities, indicating a larger number of kills depending on the amount of hides. Those from colder climates had developed greater skin preparation techniques, as it was needed to keep warm and prevent the chilling winds from getting in their lairs. Only a rare 5% of hill giants created metal armor, using the pieces of armor from defeated foes to fashion their own.[5]

Hill giants lived in caves and excavated dens, but also constructed crude buildings to live in.[5] These could be thick tents made out of livestock hides,[42] clusters of well-defended mud wattle huts, and/or log forts and rough timer steadings.[1][18] Potential advancements could include stone walls and holes from which boiling oil could be poured out from.[42] In any case, hill giant lairs were often stinking and messy, strewn with decaying carrion and broken bones and saturated with blood and the residents' filth.[7]

Relations[]

Hill giants often lived in fear of their larger giant cousins.[44] Although they did not consider it maug behavior (since for hill giants it was an inherent part of their ways) storm giants still considered the raiding practices of their lesser kin distasteful.[45] Hill giants served cloud giants, and might fight as brutes, act as fodder, battle for their amusement, or sometimes steal from humanoid lands (or "collect fair tax" as the cloud giants saw it) on their behalf.[46] Frost giants often enjoyed opportunities to mingle with other tribes so that they could show off their bravery and prowess, and particularly enjoyed their infrequent visits to hill giants since drink was so plentiful.[47]

Although ettins also worshiped the same god as hill giants, albeit a two-headed aspect of him, that did not necessarily mean that the two species had friendly relations or any special affinity for each other. They merely paid him homage as a powerful ettin, and so were not granted spells (though they could still cast spells on their faith alone) while the hill giants truly worshiped him as a deity.[48][49][50] Ettins (alongside fomorians, who were known to be enslaved for the purpose) were sometimes used as the caretakers of a tribal herd.[39][51]

Ogres were known to work for hill giants when impressed by their size or adamant ambition;[52] around half of hill giant lairs had guards, and a fifth of the time those guards consisted of 2-8 ogres.[4][5][6] Verbeeg sometimes maintained symbiotic relationships with both hill giants and ogres, and the three giant types sometimes shared so many similarities that the more ignorant members of smaller races could get them all mixed up.[30][22] The verbeeg provided greater intelligence and direction while the other types protected them. Watching them attempt to coordinate could be humorous to watch (if not their intended victim) as the infuriated verbeeg struggled to communicate with their stronger kin, who were routinely befuddled by their most basic commands.[30]

A hill giant stealing from a village.

Individuals and bands of hill giants had a tendency to be aggressively direct in their interactions, taking rather than trading. However, hill giant tribes (and some bands), often traded with other giants, including bands of ogres and other hill giants, to obtain foodstuffs, trinkets, and servants.[4][30]

- Non-Giants

Many non-giant races could end up serving hill giants. Survivors of a defeated orc tribe, given their culturally ingrained bowing before superior strength, could come under the sway of a creature like a hill giant even despite its dim wits.[53] Both hill giants and frost giants sometimes kidnapped and enslaved goliaths to force them to do menial labor, and particularly evil ones captured them specifically for the purpose of eating or sacrificing them.[54] Many hill giant tribes had discovered that dwarves were more valuable as workers than as meals, and sought to capture them for the former purpose.[55] Galeb duhrs, creatures of living stone said by some to have once been dwarves, often served hill giants.[56]

Despite their barbaric ways, hill giants still maintained a basically humanoid shape that made it easy for them to relate with more commonly civilized beings. They were never truly accepted into most civilizations, but could do well on the edges of society, forging strong and profitable lives on its frontiers.[4] They were known to serve in the military of other nations, such as in the armies of Thay.[57]

Hill giants were also known to associate with fiends. Hezrous on the Material Plane, often used their above-average intelligence and great size to recruit less intelligent giants, hill giants included.[58] Hill giants were also known to work for some of the rakshasa nobles of Tirumala[59]

- Pets

Despite their voracity, hill giants did engage in the practice of keeping pets (even if the same kinds of creatures could also end up as food).[29] These were distinct from whatever monstrous scavengers, such as oozes, otyughs, ropers, and carrion crawlers, were attracted by the stench of a hill giant den. They performed a useful "housekeeping" service, but were not domesticated or tended to, simply tolerated. Ghouls also lurked around the fringes of hill giant settlements, but were less welcome since their greater craftiness, especially when led by a ghast, could allow them to not only drag away scraps, but steal whole meals.[60] Ignoring the 20% of the time the role was filled by ogres, hill giant lairs were protected by guard animals, either dire wolves (50% of the time) or giant lizards (30% of the time).[4][5][6] Otyughs, as well as being counted among scavengers, were known to follow certain hill giants around, acting like faithful dogs.[61]

Magic[]

Hill giants normally lacked the intelligence required to learn wizardry,[62] and the majority were suspicious of magic to the point of ceremonially killing mages and destroying magic items they found.[5] However, hill giants had a few among them capable of runic magic, even if their low intelligence would normally prevent them from doing so.[31][63]

Hill giant rune cutters, known in the giant tongue as skiltgravr, stomped huge symbols into hillsides and scarred their own flesh with magical markings.[31] Those who master runic magic discover their close connection to the natural forces of the earth, granting them abilities comparable to druids. These powers allow them to, among other things, conjure landslides and repel attackers. Their magic, combined with their ability to quickly defeat and fall upon their prey, leads other giants to call them avalanchers, and sees them quickly rise to positions of power. These hill giants could be recognized by the rocks they garbed themselves in using ropes and chains.[64]

Language[]

Hill giants were known to speak the standard giant language of Jotun, but like most giant breeds, they had their own specialized dialect of the tongue, in their case Jotunhaug (which was closely interrelated to the frost giant dialect of Jotunise).[13] Although capable of speaking it, hill giants were among the giant types that were particularly prone to illiteracy due to the low value their culture placed on education and knowledge.[45] Seldom did they have the intelligence to learn to read,[22] instead telling their stories through pictograms etched into earth.[45]

About half spoke the language of ogres,[5] but most spoke a little bit of Ogre and Gnoll,[13] and the smarter ones could learn languages such as Common, Draconic, Elven, Goblin and Orc.[4]

Names[]

Common given names among hill giants included the following:[65]

- Males

- Dagg, Gulk, Hogl, Hond, Hund, Kuld, Lodd, Teldo, Vruk, and Usgut.

- Females

- Ardis, Bora, Dis, Gulkra, Gylla, Laha, Nelmyr, Telda, Teldra, Tora, and Vaere.

Religion[]

As with all giant breeds, hill giants worshiped Annam as the greatest of the giant gods and the ultimate paragon of their kind's chosen ideal. In the case of hill giants, they imagined Annam to be an enormous, master glutton, and the keeper of the grandest pantry in all reality.[38][66] Hill giant priests had recast many ancient myths and legends regarding Annam and his associates as titanic struggles based around hunting, killing, cooking, and eating.[29] In a similar vein to Annam, hill giants perceived his eldest son, Stronmaus, to be a mighty fisherman, one more youthful, energetic, and carefree than the All-Father.[67] However, the racial patron of the hill giants was Grolantor, the least of Annam's sons[60] (with the possible exception of his younger brother Karontor).[17][68]

For a long time, Grolantor (and his brother, the cloud giant deity Memnor) were forbidden from interfering with the affairs of the Jotunbrud by Annam, since when they were children, their mischievous "play" had thrusted the giants into a minor war with ogres. However, both Grolantor and Memnor managed to successfully argue that Annam's self-imposed exile had rendered his decree null and void. Once free to roam Toril, Grolantor started sending avatars amongst the Jotunbrud in the hopes of persuading giants to join him on his trouble-making outings, and naturally he received some of his warmest responses from the hill giants, who admired his courage and combat skill.[69][70] Even a hill giant who worshiped Grolantor, however was not necessarily evil or egotistical.[71]

Grolantor frequently sent avatars to his worshipers to goad them into searching for glorious battle, often leading hunting bands of hill giants himself.[69][72] Unfortunately for them, Grolantor did not extend much loyalty back to them;[69][73] he was an uncaring god who only rarely checked on their wellbeing.[74] When confronted with powerful foes, his avatars were craven until challenged, at which point they fought to the death, and this willful stupidity got both him and his followers in over their heads. He was also known to withdraw from battles at their climax out of disinterest, deserting his followers (though true devotees viewed this as a glorious chance to prove themselves) in their greatest time of need.[69][73][72][75] Though he demanded none, most hill giant priests liked to sacrifice enemies and small valuables to Grolantor anyway.[48]

The creed of Grolantor stated that the hill giants, as members of the Jotunbrud, stood above all others in the grand Ordning and were destined to rule Faerun,[73] and it was the duty of the faithful to persecute the lesser races (meaning all smaller than hill giants).[76] Furthermore, priests of Grolantor had to try and wipe out all weaker races (mostly those such as orcs, goblinoids, kobolds and similar beings) that stood in their way. They regularly organized warbands and hunting parties themselves, and[72] where they held political influence, they constantly urged their chieftains to launch invasions. Their favorite targets were goblins, dwarves, and dragons, and these raids were sometimes made against impossibly low odds.[73]

Hill giant priests could also never admit weakness or inferiority. Despite their persecution of smaller beings, hill giant shamans refused to admit that other giants were actually bigger than them, never acknowledging their superiority and instead treating them as equals.[69][73][72][76] This behavior was instilled by Grolantor, who himself refused to admit that any being was his superior, claiming that their ancient kingdom could never be reborn without such pride.[69][73] The only thing close to a formal ritual in the undisciplined and disorganized clergy of Grolantor was the believed duty of hill giant clerics to regularly prove that they could out-eat anyone in the tribe. Backing down from a fight or challenge resulted in the loss of all powers until they atoned, normally involving diving headfirst into something even more daunting.[73]

Hill giant priests existed both inside and outside the normal social structure. Often the priests of Grolantor, as they were sworn to do by the faith, took it upon themselves to find and destroy what they perceived as weakness in their society.[73] The primary responsibility of hill giant priests, however, was ensuring that their kin kept to the faith of the giant pantheon,[39] keeping them away from such blasphemously maug acts as worshiping entities like Yeenoghu.[45] Although there were no known cases of hill giants worshiping Yeenoghu, Vaprak the Rapacious (the ogre and troll god) had a few hill giant followers.[77]

Powers[]

Priests of Grolantor had access to the unique spell known as Berserk Fury, where the casting priest entered a rage and would shout strange combinations of encouragements and insults. The ranting might infect other hill giants with a similar rage (although the number affected was limited by the priest's own power) and made them stronger or tougher. However, while under the spell's affects, none would be able to retreat, would stay in melee as long as possible, and would start attacking their allies if no more enemies were around until they could recover from the rage.[73]

Hill giant shamans often had the power to manipulate the earth, using it to keep the enemy restrained, knock them from the air to the ground, and knock them prone with earthen waves.[18] Grolantor sometimes rewarded diligent shamans with a magical club that was particularly effective against dwarves. Only 5% of hill giant shamans owned such a club, and it only worked in the hands of one.[48]

Mouths of Grolantor[]

A mouth of Grolantor devouring pumpkins.

In spite of their extraordinary constitution, hill giants could become sick when their voracious eating habits led them to consume something spoiled or rotten. Their lack of experience with such things made it all the more confusing when someone in their tribes did get ill, vomiting up whatever they had carelessly consumed. When a peer could not keep down their food, hill giants believed that the sickened tribe member was being used by Grolantor as a vessel to spread his message to the world.[2]

After separating the sick individual from the rest of the tribe, often restraining them by tying them to a post or locking them in a cage, a hill giant priest or village chief would repeatedly visit them and attempt to read omens in whatever bile they retched up.[2] In actuality, there was no divine meaning behind the vomit whatsoever, as Grolantor did not communicate to his followers through signs.[72] This would continue until the giant either recovered, after which they would be set free and likely learn nothing, or until they went mad from starvation.[2]

This was no accident, as the giant was intentionally being starved in an effort to turn them into a mouth of Grolantor, a perceived manifestation of their god's endless, aching hunger.[2] Simultaneously disgraced and holy, a mouth of Grolantor was stripped of their identity and personhood to be made into a living, sacred object. They were normally kept imprisoned, and one that broke out would almost certainly kill a few hill giants before being contained again or escaping to go on an even greater rampage. Hill giants were also known to release them on raids or use them as last resort defense when under attack.[7][2]

Homelands[]

Hill giants lived in the hills and mountain valleys across the world.[1] Though they preferred temperate regions, some lived in colder climates, and they could be found in any location where inclines in the land were abundant.[4][5] They lumbered up and down the slopes and blundered through the hills and forests where they lived, often in search of food.[1] Badlands, canyons, deserts, rocky barrens, mountain passes, caves, and similar underground environments could also house hill giants, and their lairs were often made in forsaken areas.[3][4][6]

As with all giant breeds assigned a terrain to rule by Annam, hill giants had developed a natural mastery of their environment so absolute that it could be mistaken for (and sometimes was) magic. In their case, hill giants were invariably aware of the various secret passes and hidden crossways that dotted the areas surrounding their steadings.[16]

Most of Toril's giants had gathered in the regions just south of the Endless Ice Sea and west of the desert of Anauroch.[78] They were known to prowl the foothills of the Spine of the World[79] and could be found in the Ice Spires mountain range.[29] In interior Faerûn, hill giants could be found in the Cloven Mountains.[80]

Biology[]

Diet[]

On average, hill giants required more than ten times as much food as humans to survive, an even greater amount than both the larger stone and fire giants required. The reason for this disproportionate level of consumption in comparison to their size was that, over the years, hill giants had developed an excessively high metabolism.[81]

Hill giants would eat almost anything, and with little else to occupy their time they ate as much as possible. Although smart enough to avoid eating anything obviously deadly (such as poisonous creatures) they were willing to consume such disgusting things as rotten meat, decaying plants, and even mud.[1] They gleefully gorged themselves on spoiled and diseased foods as if eating dessert, oblivious to the danger, and it was only their vulture-like constitution that fended off illness.[2] They were hated and feared by farmers for their ceaseless voracity, devouring live cattle before moving on to sheep, goats, chickens, fruits, vegetables grain, and perhaps the farmers somewhere along the line.[1][81]

Hill giants mainly consumed meat,[5] which could include that of bears, griffons, ogres, humans, and demihumans among other kinds,[39] and was normally obtained through hunting.[5] Young green dragon flesh was considered a delicacy, and hill giants whose homes were covered by forests sometimes organized hunting parties to search for their lairs. In response, green dragons sometimes hunted and enslaved hill giants, who they considered to be their greatest enemy.[5][82]

Senses[]

Hill giants possessed low-light vision,[4] and, like stone and cloud giants, could detect and identify living creatures within 30 feet (9.1 meters) by scent alone.[40]

Reproduction[]

Most giants bore young in the same fashion as humans, with gestation periods for hill giants specifically being nine months.[40] Hill giant infants were completely incapable, but about as tough as a normal gnoll, while older children were about as capable as ogres.[5] Peaceful deaths were rare among hill giants (and frost giants), but they could live to be 200 years old.[8]

Sub-Races[]

A giant troll.

- Coombe giants

- Coombe giants were an eastern variant of hill giants who adapted to life within the treacherous Katakoro Shan mountains in the Hordelands. Though slightly smaller than their lowland cousins, they had developed amazing balance and dexterity, allowing them to safely traverse the steep slopes and sheer cliffs of Katakoro Shan, and even wield a weapon in each hand proficiently.[83]

- Giant trolls

- Giant trolls were crossbreeds of trolls and hill giants. Their coloration was like that of hill giants, with reddish-brown skin and red-rimmed eyes, and they were pot-bellied as opposed to being thin. They had hill giant strength (combined with trollish regeneration) but did not bite their foes They were much taller than their victims, lacked the flexibility of normal trolls, and their heads, more than any other part of their anatomy, were near identical to hill giants, lacking the sharp teeth of trolls. Like hill giants they favored clubs, and they were on good terms with strong hill giant tribes, serving as elite personal guard for the chief.[84]

Lycanthropy[]

Hill giants were known to be susceptible to all forms of lycanthropy, though were somehow immune to being afflicted with the wereraven form of the condition. Those afflicted with lycanthropy were most commonly found to be either werewolves, wereboars, wererats, or werebats. Compared to other giants afflicted with lycanthropy, hill giants were notably broad and suffered from awkward movement.[85]

Ecology[]

Usages[]

Hill giant fingers were a valuable commodity among alchemists. The fingers could be used to extract salts, that, in turn, were used to brew elixirs of hill giant strength.[86]

History[]

The lineage that would beget the hill giant race was started by the one of the mortal children of Annam All-Father and Othea, Ruk. Annam's children worked together to create Ostoria, and the kingdom's rolling hills would become the dominion of Ruk's dynasty.[15][87] The ancestors of the hill giants were enforcers who sprawled across all other lands of the time, subjugating the weaker creatures through their brute strength,[87] but the hill giant progenitors served as more than muscle. Like the higher giants, some among them created grand wonders, in their case a great stone circle that casted shadows which took the forms of hunters and animals, and which served as both a calendar and oracle.[22]

Rumors and Legends[]

Although hill giants were reviled as among the lowliest of giantkind, this, perhaps, was not always so, for hidden in many myths were suggestions that they were once much greater beings. This issue of origins was partially exasperated by the fact that the giant creator god Annam had various purported roles in the shaping of both giants and the multiverse. In some he created the entire multiverse and in others he worked with other deities to make all within it. Certain giantish myths regarding pre-history told of a time when giants were the first and only sentient lifeforms, and it was typical for their mythos to feature the existence of races of proto-giants.[17][77]

An earth titan with two hill giants by its side.

Hill giants were believed to be a weaker branch of the earth giant family, all of which nonetheless shared a connection to the primordial elements of earth and rock. The mightiest of these were the earth titans, brutes seemingly made from stone and soil.[18] Some time before -339 DR a descendant species of the hill giants known as the mountain giants broke off in the aftermath of a civil war. Although said to be smaller than hill giants, mountain giants were stronger, smarter, relatively kinder, had greater inherent magical power, and were ranked higher in the Ordning.[81][37][88][89][note 2] Some blame for the current degenerate state of the hill giants, however, was said to fall on the shoulders of Grolantor.[17]

The hill giant race was often believed to have been the result of Grolantor's collection and interbreeding of the runts of many of the earlier giantish broods.[17] It was possible that modern ettins and modern hill giants came from the same stock, as both were noted to have a common social, cultural, and religious background.[50] In some myths, Grolantor himself further polluted this foul brood by mating with various earth-bound monstrosities (including serpentine creatures and medusa-like hags), and the vile hag goddess Cegilune.[17]

Notable Hill Giants[]

Chief Guh of Grudd Haug

- Dermos, a hill giant afflicted with the wereape form of lycanthropy.[90]

- Guh, the chief of Grudd Haug, a hill giant den located along a branch of the River Dessarin, northeast of Goldenfields.[91]

- Huzza, a pirate captain in the Pirate Isles who lorded over a crew of goblins.[92]

- Imir Castdie, a hill giant member of the Zhentarim.[93]

- Moog, an old hill giant who dwelt in an abandoned tower in the Dessarin Valley.[23]

- Morg, a vampiric hill giant shaman who was banished from his tribe for being unusually handsome.[21]

- Trahnt, a gnome who was transformed into a hill giant by Halaster Blackcloak. He lived in Waterdeep and worked as a bartender at Tymora's Blessing.[94][95]

Appendix[]

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Giant heights and weights have varied wildly across editions. The heights of the major races of giants were shorter in 1st edition and 3rd edition and taller in 2nd edition and 5th edition. (4th edition did not provide information on the heights of giants.) This wiki follows the policy that Forgotten Realms sources take priority over core sources when determining giant heights. (For example, the sourcebooks Giantcraft and Volo's Guide to Monsters are considered canon when they conflict with various Monster Manuals.) The matter of weight, however, is more complicated, because—as at least a couple Dragon magazine articles have admitted (e.g., "How Heavy Is My Giant", The Dragon #13 and "Realistic Vital Statistics", Dragon #91)—some of the published values for the weights of giants are physically absurd. As is clear from basic geometry and physics, as an object is doubled in height with proportional changes in the other dimensions, its change in mass is multiplied eightfold, but this seems to have been taken into account in some sources yet not in others. In the case of a male hill giant, which, according to Realms sourcebooks, is over 16 feet (4.9 meters), the given weight is only 1,410 pounds (640 kilograms)! That is a reasonable weight for a 10.5‑foot (3.2‑meter), 1st- or 3rd-edition hill giant but is not even close for a Realmsian hill giant of 16 feet. 2nd edition's Monstrous Manual offers 4,500 pounds (2,000 kilograms) for its 16-foot hill giant, so this is the source that we choose to cite here as the only reasonable weight.

- ↑ Mountain giants appear in the adventure module, How the Mighty Are Fallen, which this wiki treats as being set in −339 DR.

Appearances[]

Adventures

Gamebooks

Video Games

Board Games

Card Games

Miniatures

Organized Play & Licensed Adventures

Gallery[]

References[]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, Christopher Perkins (2014-09-30). Monster Manual 5th edition. Edited by Scott Fitzgerald Gray. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 152, 155. ISBN 978-0786965614.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Mike Mearls, Stephen Schubert, James Wyatt (June 2008). Monster Manual 4th edition. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-7869-4852-9.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 4.31 4.32 4.33 4.34 4.35 4.36 4.37 4.38 Skip Williams, Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook (July 2003). Monster Manual v.3.5. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 123–124. ISBN 0-7869-2893-X.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 5.27 5.28 5.29 5.30 5.31 5.32 5.33 5.34 5.35 5.36 5.37 5.38 5.39 5.40 5.41 5.42 Doug Stewart (June 1993). Monstrous Manual. (TSR, Inc), p. 141. ISBN 1-5607-6619-0.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 Gary Gygax (December 1977). Monster Manual, 1st edition. (TSR, Inc), p. 45. ISBN 0-935696-00-8.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 29. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 22. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 149. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, Christopher Perkins (2014-09-30). Monster Manual 5th edition. Edited by Scott Fitzgerald Gray. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 153. ISBN 978-0786965614.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 19. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 28. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 27. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, Christopher Perkins (2014-09-30). Monster Manual 5th edition. Edited by Scott Fitzgerald Gray. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 149. ISBN 978-0786965614.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 7. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 18. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Carl Sargent (May 1992). Monster Mythology. (TSR, Inc), p. 73. ISBN 1-5607-6362-0.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 18.8 Rodney Thompson, Logan Bonner, Matthew Sernett (November 2010). Monster Vault. Edited by Greg Bilsland et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 130–133. ISBN 978-0-7869-5631-9.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 140. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ Doug Stewart (June 1993). Monstrous Manual. (TSR, Inc), p. 135. ISBN 1-5607-6619-0.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Paul Culotta (December 1996). “Children of the Night”. In Dave Gross ed. Dragon #236 (TSR, Inc.), pp. 80–88.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Tuque Games (2020). Dungeons & Dragons: Dark Alliance. Wizards of the Coast.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ Skip Williams, Jonathan Tweet and Monte Cook (October 2000). Monster Manual 3rd edition. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 12. ISBN 0-7869-1552-1.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 15. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 137. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 29.8 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 88. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Doug Stewart (June 1993). Monstrous Manual. (TSR, Inc), pp. 141, 147. ISBN 1-5607-6619-0.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 21. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 21. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 246. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 30. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 90. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 25. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 26. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 39.7 39.8 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 89–91. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 23. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 14–15. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 92. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 139. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 20. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, Christopher Perkins (2014-09-30). Monster Manual 5th edition. Edited by Scott Fitzgerald Gray. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 105. ISBN 978-0786965614.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 104. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Roger E. Moore ed. (January 1989). “Orcs Throw Spells, Too!”. Dragon #141 (TSR, Inc.), p. 28.

- ↑ Roger E. Moore ed. (January 1989). “Orcs Throw Spells, Too!”. Dragon #141 (TSR, Inc.), p. 27.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Ed Greenwood (December 1984). “The Ecology of the Ettin”. In Kim Mohan ed. Dragon #92 (TSR, Inc.), pp. 29–31.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 143. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ {{Cite book/Volo's Guide to Monsters|86-87}

- ↑ David Noonan, Jesse Decker, Michelle Lyons (August 2004). Races of Stone. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 112. ISBN 0-7869-3278-3.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford (May 29, 2018). Mordenkainen's Tome of Foes. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0786966240.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Stephen Schubert, James Wyatt (June 2008). Monster Manual 4th edition. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 114. ISBN 978-0-7869-4852-9.

- ↑ Anthony Pryor (June 1995). “Campaign Guide”. In Michele Carter, Doug Stewart eds. Spellbound (TSR, Inc.), p. 15. ISBN 978-0786901395.

- ↑ Ed Stark, James Jacobs, Erik Mona (June 13, 2006). Fiendish Codex I: Hordes of the Abyss. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 19. ISBN 0-7869-3919-2.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell, Ed Greenwood, Chris Sims (August 2008). Forgotten Realms Campaign Guide. Edited by Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 96–7. ISBN 978-0-7869-4924-3.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 29. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 70. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 59. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ James Wyatt et al. (August 2023). Bigby Presents: Glory of the Giants. Edited by Janica Carter et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 157. ISBN 978-0-7869-6898-5.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood (2020-08-25). Common Giant Names (Tweet). theedverse. Twitter. Archived from the original on 2020-08-05. Retrieved on 2021-05-16.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 43. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 47. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Colin McComb (December 1995). “Liber Malevolentiae”. In Michele Carter ed. Planes of Conflict (TSR, Inc.), pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-7869-0309-0.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 69.4 69.5 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 50. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 53. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Colin McComb (October 1994). Well of Worlds. Edited by Jon Pickens, Sue Weinlein. (TSR, Inc.), p. 62. ISBN 1-56076-893-2.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 72.4 Carl Sargent (May 1992). Monster Mythology. (TSR, Inc), p. 78. ISBN 1-5607-6362-0.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 73.3 73.4 73.5 73.6 73.7 73.8 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Jeff Grubb (July 1987). Manual of the Planes 1st edition. (TSR), p. 105. ISBN 0880383992.

- ↑ Rich Redman, James Wyatt (May 2001). Defenders of the Faith. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 95–96. ISBN 0-7869-1840-3.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 James Ward and Robert Kuntz (November 1984). Legends & Lore. (TSR, Inc), p. 93. ISBN 978-0880380508.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Carl Sargent (May 1992). Monster Mythology. (TSR, Inc), p. 74. ISBN 1-5607-6362-0.

- ↑ Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 71. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ slade, et al. (April 1996). “The Wilderness”. In James Butler ed. The North: Guide to the Savage Frontier (TSR, Inc.), p. 43. ISBN 0-7869-0391-0.

- ↑ Jim Butler (1996). The Vilhon Reach (Player's Guide). (TSR, Inc), p. 24. ISBN 0-7869-0400-3.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 Ray Winninger (September 1995). Giantcraft. Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc.), p. 16. ISBN 0-7869-0163-2.

- ↑ Doug Stewart (June 1993). Monstrous Manual. (TSR, Inc), p. 67. ISBN 1-5607-6619-0.

- ↑ Troy Denning (1990). Storm Riders. (TSR, Inc), p. 41. ISBN 0-88038-834-X.

- ↑ Doug Stewart (June 1993). Monstrous Manual. (TSR, Inc), p. 350. ISBN 1-5607-6619-0.

- ↑ Brian P. Hudson (December 1999). “The Dragon's Bestiary: Giant Lycanthropes”. In Dave Gross ed. Dragon #266 (TSR, Inc.), pp. 76–80.

- ↑ Larian Studios (October 2020). Designed by Swen Vincke, et al. Baldur's Gate III. Larian Studios.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ slade (1996). How the Mighty Are Fallen. (TSR, Inc), p. 19. ISBN 0-7869-0537-9.

- ↑ Doug Stewart (June 1993). Monstrous Manual. (TSR, Inc), p. 143. ISBN 1-5607-6619-0.

- ↑ Thomas Reid (October 2004). Shining South. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 103. ISBN 0-7869-3492-1.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, et al. (September 2016). Storm King's Thunder. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7869-6600-4.

- ↑ Curtis Scott (March 1992). Pirates of the Fallen Stars. (TSR, Inc), pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1560763208.

- ↑ Steven E. Schend, Sean K. Reynolds and Eric L. Boyd (June 2000). Cloak & Dagger. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 39. ISBN 0-7869-1627-3.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood and Steven E. Schend (July 1994). “Adventurer's Guide to the City”. City of Splendors (TSR, Inc), p. 59. ISBN 0-5607-6868-1.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood and Steven E. Schend (July 1994). “Secrets of the City”. City of Splendors (TSR, Inc), p. 14. ISBN 0-5607-6868-1.

Connections[]

Cloud • Ettin • Fire (Fire titan ) • Fog • Frost • Hill (Earth titan • Mouth of Grolantor) • Mountain • Stone • Storm • Titan

True Giant Offshoots

Ash • Craa'ghoran • Maur • Phaerlin

Giant-Kin

Cyclops (Cyclopskin) • Firbolg • Fomorian • Ogre (Oni) • Verbeeg • Voadkyn

Zakharan Giants

Desert • Island • Jungle • Ogre giant • Reef

Other Giants

Abyssal • Eldritch • Fensir • Death • Sand

Goliath • Troll (Fell • Giant troll)