However, if you can update it or think of a way to further improve it, then please feel free to contribute.

Mind flayers, also known as illithids (pronounced: /ɪlˈlɪθɪdz/ il-LITH-idz[11] ![]() listen, meaning "mind flayers" or "mind rulers" in Undercommon[12]), were evil and sadistic aberrations, feared by sentient creatures on many worlds across the multiverse due to their powerful innate psionic abilities.[1] Dwellers of deep Underdark areas, these alien humanoid-looking beings sought to expand their dominion over all other creatures, controlling their minds to use them as hopeless slaves and devouring their brains for sustenance.[2]

listen, meaning "mind flayers" or "mind rulers" in Undercommon[12]), were evil and sadistic aberrations, feared by sentient creatures on many worlds across the multiverse due to their powerful innate psionic abilities.[1] Dwellers of deep Underdark areas, these alien humanoid-looking beings sought to expand their dominion over all other creatures, controlling their minds to use them as hopeless slaves and devouring their brains for sustenance.[2]

Their natural psionic abilities also made mind flayers respected in the eyes of the drow, beholders, duergar, and other dominant races of the Underdark.[13]

Description

Mind flayers were humanoid in appearance but with an octopus-like, ridged head with four tentacles surrounding a lamprey-like mouth.[1][4][14] They were warm-blooded amphibians,[6] whose blood had a silvery-white color.[15]

Their hands had long, reddish fingers and lacked the index finger,[7][16] and their feet were two-toed and webbed.[16] Mind flayer eyes were extremely sensitive to bright light, and they considered it painful, a characteristic that some githyanki scholars attributed to the fact that their alien anatomy focused light in a strange way.[10] Their vision was also more sensitive to the recognition of geometric patterns than that of other humanoids.[17]

Mind flayers that were healthy from brain-rich diets excreted a kind of slimy mucous substance that coated their mauve skins.[1][7]

Personality

Mind flayers were tyrants, slavers, and planar voyagers. They viewed themselves as masterminds, controlling, harvesting, and twisting the potential of other creatures to further their evil and far-reaching goals.[1] Although they cooperated to achieve a goal, they would back away at the first sign that something was not profitable to their self-serving interests.[4]

Mind flayers were aggressive and elitist and would attempt to mentally dominate any non-slave, non-illithid that they met.[1][4] However, despite their aggressiveness, illithids were ultimately a paranoid and fearful race. They were relentlessly hunted by the gith, so any mind flayer colony's first priority was concealment and survival.[2]

Emotionally, a mind flayer appeared detached and calm, showing no signs of passion or loss of control. However, sometimes they showed great bouts of anger, which were difficult to identify as true emotions or mere display. The mind flayer mind knew only negative emotions, only finding fulfillment in the angry and sadistic act of consuming a brain. The closest to happiness any mind flayer could know was in its pride and in satisfying its curiosity.[19]

Combat

A mind flayer eating.

In spite of their lack of physical abilities, mind flayers were feared by all beings in the Underdark because of their great mental prowess. In addition to the small array of mind-affecting spells that every illithid had at its disposal to take control of its prey, they also frequently employed a powerful mind blast to affect a multitude of foes. The mind flayer's mind blast was a 60‑foot (18‑meter) cone that stunned anyone caught within it.[1][4]

Normally, a mind flayer would use its mind blast ability to stun a few foes and then drag them away to feed. Once it had its victims, it would attach all of its tentacles to the head of one of its prey. Then, the mind flayer sucked out the brain, instantly killing the creature, as long as it only had one head. The mind flayer used its other spells mainly to enslave its minions and keep them under total control. It also used its spells on the battlefield.[1][4]

Their abundant psionic powers allowed them to levitate at will, as well as to detect the thoughts of nearby creatures and to dominate or charm any kind of creature in their vicinity. Additionally, there were reports of mind flayers capable of controlling other by power of suggestion.[1][4] They were also capable of teleporting themselves to other planes of existence by plane shifting.[1]

Some illithids dedicated themselves to studying and honing their innate abilities. Known as illithid psions, they were capable of even more remarkable feats of psionic power, including telekinetic abilities akin to mage hand and telekinesis; further mental control abilities such as charm person, command, sanctuary, fear, crown of madness, phantasmal force, and confusion; and even divination abilities such as guidance, true strike, see invisibility, clairvoyance, and scrying.[2]

Ecology

The skull of a mind flayer.

Physiology

Illithids fed on the brains of sentient creatures (mainly humanoids). This was the only kind of nourishment that could sustain the mind flayer physiology, which required hormones, enzymes, and psychic energy that only brain tissue could provide. Feeding was a euphoric experience for a mind flayer, as it absorbed its victim's memories, personality, and fears.[1] It was also viewed by them as the ultimate form of dominance over another creature.[10]

A mind flayer needed to consume at least one intelligent brain per month in order to remain healthy. Malnourished mind flayers died after four months of brain deprivation.[20] The psionic energy also left traces of the original prey's individuality on a mind flayer's sense of culture and aesthetics.[2]

Reproduction

An illithid tadpole preparing to enter a human host.

Illithids were all sexless, without male or female biological sex,[21] and once or twice in their life they would lay a clutch of eggs from which tadpoles hatched. The tadpoles were kept in the elder brain tank, where they were fed brains by caretakers and engaged in cannibalism for around ten years.[6] The elder brain also fed exclusively on tadpoles. Tadpoles that survived to maturity were put through the ceremony of ceremorphosis, where each was implanted into a humanoid victim and devoured its brain, taking its place and merging with the body to transform it into a new illithid. Only some humanoid species were suitable hosts for illithid tadpoles.[6][2][22]

The multiplication of mind flayer colonies happened when a tadpole, quite rarely, through ceremorphosis, created a more powerful form known as an ulitharid (meaning "noble devourer" in Undercommon),[12] which was biologically bigger, stronger, and more powerful and cunning than regular mind flayers. They possessed six face tentacles instead of the regular four. Most notably, however, they were not controlled by the elder brain. The appearance of an ulitharid caused a burst of growth in both the colony's size and capabilities. Elder brains grudgingly accepted the appearance of a potential rival, because eventually the ulitharid broke off from the colony. When doing so, it took a few mind flayers with it and sought to establish a new colony in a distant location from the original. Eventually, the ulitharid transformed into a new elder brain.[2][23]

A mind flayer with a tadpole and a thrall holding down a drow for ceremorphosis.

If, for some reason, a mature tadpole did not undergo the process of ceremorphosis, it became a ravenous predatory creature known as an illithocyte or, if allowed to grow out of control, a neothelid. These creatures were considered abhorrent by the illithids and were mercilessly hunted.[2][24]

Illithid Monsters

Mind flayers constantly experimented with transforming other creatures and implanting their tadpoles into different races, producing a large variety of thralls.[2][24]

The process of ceremorphosis yielded a new mind flayer only if the tadpole was applied to certain compatible types of humanoids. Normally, attempting ceremorphosis on an incompatible creature resulted in death for both the host and the tadpole.[25] However, illithid research showed that it was sometimes possible to perform ceremorphosis even on an incompatible host.[26] Creatures that underwent successful ceremorphosis but did not produce mind flayers were referred to as ceremorphs, or "flayer-kin".[27] Some known types of ceremorphs included:

| Original Creature | Resulting Monster |

|---|---|

| Inserting a tadpole into a… | …produced a… |

| Human Elf (including drow) Githyanki Githzerai Grimlock Gnoll Goblinoid Orc |

Mind flayer[25][28] or Ulitharid (rarely)[29] |

| Beholder | Mindwitness[2] |

| Chuul | Uchuulon[30] |

| Deep gnome | Mozgriken[27] |

| Dragon | Brainstealer dragon[31] |

| Lizardfolk | Tzakandi[27] |

| Roper | Urophion[32] |

- Brainstealer dragon

- The result of implanting a tadpole in a captured dragon.[31]

- Mindwitness

- The result of implanting a tadpole in a captured beholder.[2]

- Mozgriken

- The result of a tadpole being inserted into a deep gnome and then subjected to psychic surgery that channeled energy from the Shadowfell.[33]

- Tzakandi

- The result of a tadpole being inserted into lizardfolk.[26]

- Uchuulon

- The result of a chuul being implanted with a tadpole.[30]

- Urophion

- A roper that had survived the tadpole implantation process.[32]

In addition to ceremorphosis, many illithid colonies experimented with altering creatures in a variety of ways to produce new monsters that could serve them. Most such experiments resulted in shapeless abominations, but a few were occasionally successful and produced viable servants.[34] Some known illithid-created monsters included:

- Brain golem

- A large humanoid-shaped construct made entirely of brain tissue. They sprouted from the elder brain to conduct specific tasks or as a defense measure.[35][36]

- Cranium rat

- Regular rats bombarded with psionic energy. They could form intelligent swarms that grew smarter as they accumulated experiences.[37]

Nihiloor and its pet intellect devourers.

- Intellect devourer

- Creatures created by subjecting a slave's brain to a ritual that caused it to sprout legs. They were employed as guards or as bait to lure outsiders into a colony. The larval form of an intellect devourer, known as an ustilagor, was considered a delicacy in Oryndoll.[2][24][38]

- Mind worm

- An aquatic monster that resembled a pale, smaller purple worm. They were capable of attacking creatures through any reflective surface, even across different planes.[39]

- Nerve swimmer

- A modification of an immature tadpole. Used by some mind flayer colonies such as Oryndoll as a torture instrument.[24]

- Nyraala golem

- A large partially-humanoid construct that did not require the tissue of the elder brain. They almost rivaled brain golems in power and were more numerous in known illithid cities.[40]

- Oblex

- The result of experimentation with oozes. They fed on their victims' memories and could assume their shapes and identities.[41]

There were also creatures thought to have originated in the same world as illithids and related to them in the same way that animals were akin to humans. These creatures, known as illithidae, were sometimes found near mind flayer settlements. It was unknown whether they were naturally attracted by the colonies or if they had been domesticated by the mind flayers. Some sages believed that gas spores had been created by mind flayers as well.[42][43]

If mind flayers became undead, their new forms were also alien and in many ways different from other undead creatures.[44] Typical undead mind flayers included:

- Alhoon

- A mind flayer who decided to follow the path of wizardry could achieve a lesser form of lichdom and become an undead creature known as an alhoon. It was also possible, although rare, for an extremely powerful mind flayer wizard to become a true lich, also known as an illithilich. These terrible beings were so rare that usually people did not make that distinction.[45][46]

- Vampiric illithid

- A feral undead illithid with vampiric powers. Its origin was unknown.[44]

Society

Individual mind flayers were rarely found alone; rather, they were usually accompanied by two or more slaves mentally bound to them. Typical enslaved races found among mind flayers included grimlocks, ogres, quaggoths, and troglodytes.[1][4] These enslaved species had in common the fact that they were not typically considered edible by the illithids.[10]

Mind flayer communities (also called "colonies") typically ranged in size from two hundred to two thousand, and that was counting only the illithids. Each mind flayer in the community likely had at least two slaves to do its bidding. In these communities, the number of slaves often far outstripped the number of mind flayers.[47] For example, the illithid city of Oryndoll had a total population of just under 24,000 as of 1372 DR, but mind flayers accounted for only about 4,300 of that number.[13]

Mind flayer colonies operated as a single hive mind, with control centralized by an elder brain, a singular entity that exerted its telepathic control simultaneously over all mind flayers within a radius of 5 miles (8 kilometers).[1] The elder brain was the heart of the community. Held in a pool of briny fluids, the elder brain consisted of all the brains of the dead mind flayers in the colony.[4] It served as the center of the communication network, relaying information received from one mind flayer to the entire colony, storing all the collective knowledge of the colony, and issuing commands to individual mind flayers. The degree of control and organization exerted by the elder brain over a mind flayer community was so absolute that it was more convenient to think of a mind flayer colony as a single individual: the elder brain.[2]

Although mind flayers willingly came together to achieve an end, they were always vying for more control in the community, but even then they were always beneath the elder brain.[4] While individual mind flayers might have, at one time in their past, retained a certain degree of independent thought, after the collapse of the illithids' empires it was generally agreed upon by them that their survival required complete obedience to the elder brain.[2]

Within the colonies, mind flayers organized themselves in ideological factions known as Creeds, which aligned with each particular illithid's abilities and philosophy. Representatives of the various Creeds organized themselves in "Elder Concords", which, under the auspices of the elder brain, coordinated the colony's various activities. In cases when multiple colonies pursued common objectives, a "Grand Elder Concord" was formed.[48]

An illithid oversees the transport of an elder brain by quaggoth slaves.

When problems arose or the mind flayers wished to discover some secret, they formed "inquisitions", a team of mind flayers, not unlike an adventuring party. Each mind flayer used its own talents and abilities to achieve the inquisition's goal. If a situation was too large for just an inquisition to handle, the mind flayer community put together a "cult". A cult was much larger than an inquisition and was spearheaded by two mind flayers who constantly vied for greater power within it.[4] This type of mission, which put mind flayers temporarily out of reach from the elder brain, was regarded as dangerous but highly profitable if successful.[2]

If a mind flayer remained out of reach from its elder brain, it was possible for it to reacquire its free will. These so-called renegade illithids could go on to establish their own colonies or, free from the elder brain's arrogant supremacy, even seek cooperation with other species. This new personality and any alliances that were made instantly vanished as soon as the renegade illithid fell back under control of an elder brain.[2]

Language and Names

Illithids were capable of speaking Undercommon and Deep Speech but preferred telepathic communication.[1][4] They also had a form of written language called Qualith, which consisted of patterns of four lines imbued with psionic energy, capable of conveying not only text but also the author's thoughts. Without the use of magic, it could only be read by other illithids.[1][2]

Mind flayer names were strains of thoughts and images that identified them to other members of the race. Since these names were too complex to be pronounced or even expressed in words, other races of the Underdark adopted rough translations in Undercommon by usually combining descriptive words that conveyed the general idea of the mind flayers' original names in order to identify them.[12] Sometimes, the illithids themselves chose to adopt pronounceable names for the benefit of their thralls or to instill fear in their enemies.[2]

Magic

A mind flayer sorcerer.

Mind flayers considered arcane magic an abomination. They viewed it as an inferior and corrupt form of psionic power that should disappear from the universe once the illithids regained control of it. It was speculated that this hatred was related to the role of magic in the gith rebellion.[2]

Arcane magic was especially sought out by renegade illithids looking for ways to shield themselves from the elder brain's influence.[2] Although most mind flayer arcanists were wizards, a few were also born with the gift of sorcery. Because a mind flayer sorcerer was naturally more intelligent than other mind flayers, it was better able to resist psionics. For the most part, an illithid with the gift of sorcery would use defensive spells such as greater invisibility and resist energy, as well as spells to further hinder enemies, such as ray of exhaustion and touch of idiocy.[4]

Mind flayers were capable of channeling their psionic abilities to craft their own version of magic items. As a security measure, these items could only be used by the illithids or their thralls. They had a variety of abilities and applications, such as the survival mantle, which allowed the wearer to breathe in a vacuum, or mind carapace armors, which protected the wearer's mind as well as its body.[2] They also had the ability to craft psionic seals, a type of brand that granted its wearer a variety of abilities.[49] Other items included mind blades, shields of far sight[2] psychic swords, psychic reservoirs, resonance stones, tentacle extensions, gauntlets of Tyla'zhus, tessadyle robes and tendril rings of Ilsensine.[49] Some illithids also experimented with symbiont creatures in order to create living carapaces of armor.[50]

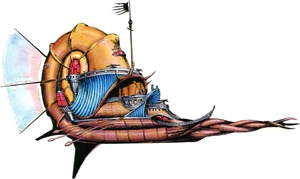

A nautiloid spelljammer, used by mind flayers to travel through the Material and Astral planes.

A rare and most treasured item in a mind flayer colony was a flying ship known as a nautiloid.[2] Mind flayers once had a massive presence in space and commanded countless of these conch-shaped spelljammers. In fact, spacefaring mind flayers were sometimes quite different from their land-bound counterparts and acted more as traders than conquerors.[49][51] However, incessant hunting by the gith and the fact that mind flayers lost the means to build them or acquire them from the arcane caused them to almost disappear.[2][52]

Religion

As a race of planar travelers, mind flayers did not worship entities from the Outer Planes as deities and did not share the same mythical thoughts about the afterlife. Instead, an illithid's last desire upon death was to be rejoined with its elder brain, thus attaining a form of immortality by having its life experiences merged into the elder brain's consciousness. Elaborate funerary jars, also known as brain canisters,[53] with the individual's biography inscribed in Qualith were commonly used by mind flayer colonies to preserve a dead mind flayer's brain until it was consumed by the elder brain.[2]

A mind flayer placing the brain of a slain comrade in a funerary jar.

However, mind flayers revered two manifestations of psionic ideals in a form resembling worship. These entities were not exactly deities but were revered as such and were capable of granting divine powers to their followers, even non-illithid ones.[2][54]

The broader entity was known as Ilsensine, which embodied a mastery of one's own mind and a union with universal knowledge. Mind flayer colonies interpreted this concept in different ways.[2] Some viewed it as a promise of power and domination to its followers, a feature that was also attractive to non-illithid followers.[54] Others interpreted these objectives as attainable through dominance or replacement of the deities associated with knowledge.[2] The influence of Ilsensine was important in the conflict between mind flayers of Oryndoll and the duergar. In the time when they had invaded the shield dwarf kingdom of Shanatar and captured many shield dwarves, the mind flayers had no gods. However, when the dwarves began to stage uprisings and rebellions, the city was plunged into chaos. The only reason it did not fall to the duergar rebellions was because of the sudden appearance of the mind flayer god Ilsensine. Since Ilsensine's appearance, the mind flayers became deeply religious and began to develop formidable psionic powers.[55] Ilsensine's favored proxy was Lugribossk.[56]

A smaller sect of mind flayers revered another entity called Maanzecorian. It embodied a complete comprehension of knowledge and the simultaneous access to memory, thought, and aptitude.[2] It was also viewed by the illithids as a keeper of secrets. Its essence was killed by Tenebrous, the undead shadow of the demon lord Orcus sometime in the mid-14th century DR,[57] though this fact was unknown to most at the time.[58] However, in the late 15th century DR, mind flayer colonies dedicated to Maanzecorian were again common.[2]

Some mind flayers viewed the perfect memory of the aboleths as a manifestation of Maanzecorian, which led to several conflicts between them.[2]

History

The illithid race was extremely old and predated recorded history, as ancient texts that did not mention younger races already mentioned illithids. The mind flayers themselves appeared not to have much knowledge of their eldritch origins.[59]

Origins

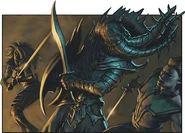

A githyanki attacking a mind flayer.

Some sages theorized that mind flayers were aliens from an unimaginably distant future, who had come back in time to prevent their extinction from being brought upon by the end of the universe. By the use of a powerful spell, they sent their great spelljamming fleet back in time, arriving at different time periods in different crystal spheres and reestablishing their empires. This interpretation was consistent with the fact that aboleths, even with their perfect racial memories, did not remember the beginnings of the illithid race.[60]

Others believed that, because of their advanced technology and ships, illithids were a cursed, inbred mutant offspring of humans from an ancient and distant crystal sphere known as Clusterspace,[61] forced to live in the underground depths of their world, honing their mental skills and experimenting with psionic powers for ages until the hate for their oppressors caused them to seek vengeance and set out to conquer the universe.[62]

Other scholars dismissed the origin myths of illithids as a mutant breed of humans, instead believing that they might have originated in the Far Realm, (referred to as the "Outside" in the Sargonne Prophecies,)[59] or at least had been warped by it.[63] A group of mind flayers who later reached the Far Realm on a nautiloid returned with drastically changed bodies, minds, and goals, worshiping an unknown entity referred to as Thoon.[64]

Most origin myths agreed that, an untold number of millennia in their past, mind flayers were the most powerful race in the Inner Planes, commanding vast empires from the Astral and Ethereal planes that spanned multiple worlds, kept under control by their nautiloids.[2][59] The Planetreader's Primer, a book of ancient lore allegedly published in Sigil, further stated that the vast mind flayer empire also threatened the boundaries of the Outer Planes, at some point even disturbing the Blood War.[65][66]

At some point, the gith, their most prominent slave race, rebelled and brought down the entirety of the mind flayer empires in the Astral Plane in less than a year. The surviving mind flayer enclaves in the Material Plane were constantly and mercilessly hunted down by raiding parties from both the githyanki and githzerai factions, bringing the illithid race to the brink of extinction.[2][59]

Recorded History

Sometime around −11,000 DR, illithid refugees from the planet Glyth arrived on Toril and founded the city of Oryndoll in the Underdark.[67]

The dwarves of Clan Duergar succumb to the power of the elder brain of Oryndoll.

In −8100 DR, the illithids from Oryndoll attacked eastern Shanatar, starting the twenty-year long Mindstalker Wars. The war ended with a retreat of the illithids, but they managed to capture and enslave the dwarves from Clan Duergar, who were experimented with during the following millennia and eventually became the duergar subrace.[68] Around −4000 DR, the duergar slaves rebelled and broke free from the mind flayers, nearly destroying Oryndoll, which narrowly escaped destruction thanks to the appearance of an avatar of Ilsensine.[69] The duergar subsequently founded several holds across the northern Underdark.[70] In −1850 DR, the city of Oryndoll was attacked by the duergar as part of a series of attacks against all their enemies.[71]

The mind flayers had the first contact with the Netherese in −1064 DR.[72]

In 153 DR, an army of illithids and lycanthrope slaves invaded and conquered the dwarven city of Gauntlgrym.[73] The ruined city remained disputed by groups of aboleths, duergar, drow, and illithids until it was retaken by the Companions of the Hall in the late 15th century DR.[74]

In 1154 DR, the town of Ch'Chitl was founded by an illithid cult seeking to establish a partnership with Skullport.[75] The city's elder brain planned to use the town as a foothold in a move to enslave Waterdeep. In 1250 DR, however, the city was attacked by githyanki, who mortally injured the elder brain and derailed their invasion plans.[76] In 1385 DR, the city was ravaged by the Spellplague, which created horribly mutated mind flayers with extraordinary psionic abilities.[77]

A mind flayer of Thoon pursued very different goals from a regular illithid.

Sometime in the mid-13th century DR, the illithids managed to reestablish their domain on Glyth, from where they conducted selective breeding experiments with oortlings.[78] Around that same time, there was also an illithid colony in a free-standing object in Realmspace known as the Skull of the Void, in which they performed breeding experiments on beholders. Decades of consumption of the beholders' brains conferred to the illithid inhabitants and their descendants the ability to levitate.[79] Sometime in the late 14th century DR, Glyth was laid to waste by the elder evil known as Atropus, who had been concealed in one of the planet's rings.[80] However, by the next century, mind flayer colonies were again present on the planet.[81]

During the Time of Troubles, Oryndoll was once again visited by an avatar of Ilsensine, an event that ushered a large expansion in the city's creeds.[69] Shortly afterward, members of the Loretaker Creed traveled to the Caverns of Thought in search of Ilsensine but returned as firm followers of Thoon.[82]

In the late 15th century DR, mind flayers had lost the knowledge of how to construct their plane-crossing nautiloid vessels. Since the illithids knew that the end of the nautiloids would mean their permanent exile in the Material Plane, a few colonies were dedicated to rediscovering the secrets of nautiloid construction.[2]

Notable Mind Flayers

Captain N'ghathrod and the miniature giant space hamster aboard the Scavenger.

- Galuum, an inhabitant of the Ryxyg enclave sent to enslave duergar in the Waydown in the late 15th century DR.[83]

- Grazilaxx, a member of the Society of Brilliance.[84]

- Methil El-Viddenvelp, chief advisor to House Baenre on matters concerning the borders of Menzoberranzan.[85]

- Captain N'ghathrod of the Scavenger, a space pirate native to Glyth.[81]

- Nihiloor, a mind flayer who worked for the Xanathar's Thieves' Guild. It was fond of creating intellect devourers and setting them loose throughout Waterdeep.[86]

- Ralayan, an alhoon who served as right hand to Priamon Rakesk of the Twisted Rune.[87][88]

- Vestress, a rogue illithid who served the Kraken Society as Regent of Ascarle.[89]

- Yharaskrik, a mind flayer involved in the destruction of Crenshinibon in 1366 DR.[90]

- Xetzirbor, an inhabitant of the Cyrog enclave who journeyed to Gravenhollow to save the city's elder brain from death in the late 15th century DR.[91]

Appendix

Appearances

- Card Games

- AD&D Trading Cards

- Novels

Referenced only

- Video Games

- Eye of the Beholder • Eye of the Beholder II: The Legend of Darkmoon • Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace • Menzoberranzan • Descent to Undermountain • Icewind Dale • Baldur's Gate II: Shadows of Amn • Baldur's Gate II: Throne of Bhaal • Neverwinter Nights: Hordes of the Underdark • Neverwinter Nights 2 • Neverwinter Nights 2: Mask of the Betrayer • Baldur's Gate: The Black Pits • Neverwinter • Sword Coast Legends • Baldur's Gate: Siege of Dragonspear • Idle Champions of the Forgotten Realms • Baldur's Gate III

- Adventurers League

- The Occupation of Szith Morcane • The Malady of Elventree • Writhing in the Dark

Further Reading

- Clifford Horowitz (November 2003). “Brain Power”. In Chris Thomasson ed. Dragon #313 (Paizo Publishing, LLC), p. 46–52.

External Links

Mind flayer article at the Eberron Wiki, a wiki for the Eberron campaign setting.

Mind flayer article at the Eberron Wiki, a wiki for the Eberron campaign setting.

Gallery

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, Christopher Perkins (2014-09-30). Monster Manual 5th edition. Edited by Scott Fitzgerald Gray. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 221–222. ISBN 978-0786965614.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 2.31 2.32 2.33 2.34 2.35 2.36 Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 71–81. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Stephen Schubert, James Wyatt (June 2008). Monster Manual 4th edition. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-0-7869-4852-9.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 Skip Williams, Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook (July 2003). Monster Manual v.3.5. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 186–188. ISBN 0-7869-2893-X.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell (April 2004). Expanded Psionics Handbook. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 204. ISBN 0-7869-3301-1.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 Doug Stewart (June 1993). Monstrous Manual. (TSR, Inc), p. 251. ISBN 1-5607-6619-0.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Gary Gygax (December 1977). Monster Manual, 1st edition. (TSR, Inc), p. 70. ISBN 0-935696-00-8.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 40–41. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Stephen Schubert, James Wyatt (June 2008). Monster Manual 4th edition. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 188. ISBN 978-0-7869-4852-9.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Roger E. Moore (October 1983). “The Ecology of the Mind Flayer”. In Kim Mohan ed. Dragon #78 (TSR, Inc.), pp. 66–68.

- ↑ Frank Mentzer (January 1985). “Ay pronunseeAYshun gyd”. In Kim Mohan ed. Dragon #93 (TSR, Inc.), p. 26.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Owen K.C. Stephens (March 2001). “By Any Other Name: Races of the Underdark”. In Dave Gross ed. Dragon #281 (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 48–49.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Bruce R. Cordell, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, Jeff Quick (October 2003). Underdark. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 20. ISBN 0-7869-3053-5. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "UD" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), p. 8. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), p. 112. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), p. 9. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ Nigel Findley (September 1991). Into the Void. (TSR, Inc.), p. 69. ISBN ISBN 1-56076-154-7.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), p. 40. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Jacobs, and Steve Winter (April 2005). Lords of Madness: The Book of Aberrations. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 63–64. ISBN 0-7869-3657-6.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), p. 14. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ Nigel Findley (September 1991). Into the Void. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 91–92. ISBN ISBN 1-56076-154-7.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Jacobs, and Steve Winter (April 2005). Lords of Madness: The Book of Aberrations. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 63. ISBN 0-7869-3657-6.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 175. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Kevin Baase, Eric Jansing, Oliver Frank, and Bill Halliar (November 2005). “Monsters of the Mind – Minions of the Mindflayers”. In Erik Mona ed. Dragon #337 (Paizo Publishing), pp. 25–35.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), p. 11. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Christopher M. Schwartz (January 1999). “The New Illithid Arsenal”. In Bill Slavicsek ed. Dragon #255 (TSR, Inc.), p. 33.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Eric L. Boyd (November 1999). Drizzt Do'Urden's Guide to the Underdark. Edited by Jeff Quick. (TSR, Inc.), p. 22. ISBN 0-7869-1509-9.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Jacobs, and Steve Winter (April 2005). Lords of Madness: The Book of Aberrations. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 63. ISBN 0-7869-3657-6.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), p. 15. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Richard Baker, Joseph D. Carriker, Jr., Jennifer Clarke Wilkes (August 2005). Stormwrack. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 163–164. ISBN 07-8692-873-5.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Kevin Baase, Eric Jansing, Oliver Frank, and Bill Halliar (November 2005). “Monsters of the Mind – Minions of the Mindflayers”. In Erik Mona ed. Dragon #337 (Paizo Publishing), p. 25.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), p. 18. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ Christopher M. Schwartz (January 1999). “The New Illithid Arsenal”. In Bill Slavicsek ed. Dragon #255 (TSR, Inc.), p. 34".

- ↑ Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 78. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 17, 88, 92. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ Eric Cagle, Jesse Decker, James Jacobs, Erik Mona, Matthew Sernett, Chris Thomasson, and James Wyatt (April 2003). Fiend Folio. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 85–86. ISBN 0-7869-2780-1.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 133. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, Christopher Perkins (2014-09-30). Monster Manual 5th edition. Edited by Scott Fitzgerald Gray. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 191. ISBN 978-0786965614.

- ↑ Kevin Baase, Eric Jansing, Oliver Frank, and Bill Halliar (November 2005). “Monsters of the Mind – Minions of the Mindflayers”. In Erik Mona ed. Dragon #337 (Paizo Publishing), pp. 29–31.

- ↑ Christopher M. Schwartz (January 1999). “The New Illithid Arsenal”. In Bill Slavicsek ed. Dragon #255 (TSR, Inc.), p. 32".

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford (May 29, 2018). Mordenkainen's Tome of Foes. Edited by Kim Mohan, Michele Carter. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 217–219. ISBN 978-0786966240.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Jacobs, and Steve Winter (April 2005). Lords of Madness: The Book of Aberrations. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 154–157. ISBN 0-7869-3657-6.

- ↑ Stephen Inniss (October 1989). “The Dragon's Bestiary: All life crawls where mind flayers rule”. In Roger E. Moore ed. Dragon #150 (TSR, Inc.), pp. 12–16.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Richard Baker, James Jacobs, and Steve Winter (April 2005). Lords of Madness: The Book of Aberrations. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 160–161. ISBN 0-7869-3657-6.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-0786966011.

- ↑ James Wyatt, Rob Heinsoo (February 2001). Monster Compendium: Monsters of Faerûn. Edited by Duane Maxwell. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 89–90. ISBN 0-7869-1832-2.

- ↑ Skip Williams, Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook (July 2003). Monster Manual v.3.5. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 188. ISBN 0-7869-2893-X.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (November 1999). Drizzt Do'Urden's Guide to the Underdark. Edited by Jeff Quick. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-7869-1509-9.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 80–85. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ Penny Williams (June 2003). “Armed to the Tentacle”. In Jesse Decker ed. Dragon #308 (Paizo Publishing, LLC), pp. 52–60.

- ↑ Jeff Grubb (August 1989). “Lorebook of the Void”. Spelljammer: AD&D Adventures in Space (TSR, Inc.), p. 61. ISBN 0-88038-762-9.

- ↑ Jeff Grubb (August 1989). “Lorebook of the Void”. Spelljammer: AD&D Adventures in Space (TSR, Inc.), p. 67. ISBN 0-88038-762-9.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Jacobs, and Steve Winter (April 2005). Lords of Madness: The Book of Aberrations. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 67–68. ISBN 0-7869-3657-6.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Bruce R. Cordell (April 2004). Expanded Psionics Handbook. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 222. ISBN 0-7869-3301-1.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood, Sean K. Reynolds, Skip Williams, Rob Heinsoo (June 2001). Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting 3rd edition. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 213. ISBN 0-7869-1836-5.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), p. 89. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ Monte Cook (December 2, 1997). Dead Gods. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 37. ISBN 978-0786907113.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), p. 41. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 Bruce R. Cordell (April 1998). The Illithiad. Edited by Keith Francis Strohm. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 36–40. ISBN 0-7869-1206-5.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Jacobs, and Steve Winter (April 2005). Lords of Madness: The Book of Aberrations. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 7, 30, 69. ISBN 0-7869-3657-6.

- ↑ Sam Witt (1993). “The Astrogator's Guide”. In Michele Carter ed. The Astromundi Cluster (TSR, Inc.), pp. 4–5. ISBN 1-56076-632-8.

- ↑ Sam Witt (1993). “Adventures in the Shattered Sphere”. In Michele Carter ed. The Astromundi Cluster (TSR, Inc.), pp. 48–51. ISBN 1-56076-632-8.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, Christopher Perkins, James Wyatt (2014). Dungeon Master's Guide 5th edition. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 68. ISBN 978-0786965622.

- ↑ (July 2007). Monster Manual V. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 104. ISBN 0-7869-4115-4.

- ↑ Richard Baker, James Jacobs, and Steve Winter (April 2005). Lords of Madness: The Book of Aberrations. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 70–71. ISBN 0-7869-3657-6.

- ↑ Monte Cook (January 1996). A Guide to the Astral Plane. Edited by Miranda Horner. (TSR, Inc.), p. 44. ISBN 0-7869-0438-0.

- ↑ Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Bruce R. Cordell, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, Jeff Quick (October 2003). Underdark. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 168–169. ISBN 0-7869-3053-5.

- ↑ Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, Adam Lee, Richard Whitters (September 1, 2015). Out of the Abyss. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 121. ISBN 978-0-7869-6581-6.

- ↑ Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 126. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ Bruce R. Cordell, Ed Greenwood, Chris Sims (August 2008). Forgotten Realms Campaign Guide. Edited by Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-0-7869-4924-3.

- ↑ Dale "slade" Henson (April 1991). Realmspace. Edited by Gary L. Thomas, Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc), p. 39. ISBN 1-56076-052-4.

- ↑ Dale "slade" Henson (April 1991). Realmspace. Edited by Gary L. Thomas, Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc), p. 54. ISBN 1-56076-052-4.

- ↑ Schwalb, Robert J. (December 2007). Elder Evils. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7869-4733-1.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Christopher Perkins (November 2018). Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 250. ISBN 978-0-7869-6626-4.

- ↑ (July 2007). Monster Manual V. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 125. ISBN 0-7869-4115-4.

- ↑ Lisa Reinke (2015-11-01). The Malady of Elventree (DDEX3-08) (PDF). D&D Adventurers League: Rage of Demons (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 15–16, 31.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, Adam Lee, Richard Whitters (September 1, 2015). Out of the Abyss. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-7869-6581-6.

- ↑ R.A. Salvatore, Michael Leger, Douglas Niles (1992). Menzoberranzan (The Houses). Edited by Karen S. Boomgarden. (TSR, Inc), p. 18. ISBN 1-5607-6460-0.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, James Haeck, James Introcaso, Adam Lee, Matthew Sernett (September 2018). Waterdeep: Dragon Heist. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 212. ISBN 978-0-7869-6625-7.

- ↑ Steven E. Schend (January 1997). Undermountain: Stardock. Edited by Bill Olmesdahl. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 14–15. ISBN 0-7869-0451-8.

- ↑ Steven E. Schend (August 1997). “Book Three: Erlkazar & Folk of Intrigue”. In Roger E. Moore ed. Lands of Intrigue (TSR, Inc.), p. 22. ISBN 0-7869-0697-9.

- ↑ Elaine Cunningham (May 1998). Tangled Webs. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 84. ISBN 0-7869-0698-7.

- ↑ R.A. Salvatore (October 2000). Servant of the Shard. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 336–337. ISBN 0-7869-1657-5.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, Adam Lee, Richard Whitters (September 1, 2015). Out of the Abyss. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 154, 158. ISBN 978-0-7869-6581-6.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Mike Mearls, et al. (November 2016). Volo's Guide to Monsters. Edited by Jeremy Crawford, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 76. ISBN 978-0786966011.

Connections

Ceremorphs

Brainstealer dragon • Gnome ceremorph • Gnome squidling • Illithiderro • Mindwitness • Mozgriken • Tzakandi • Uchuulon • Urophion • Yuan-tillithid

Related Creatures

Brain golem • Cranium rat • Nyraala golem • Illithidae • Illithocyte • Intellect devourer • Mind worm • Neothelid • Nerve swimmer • Oblex • Oortling • Ustilagor