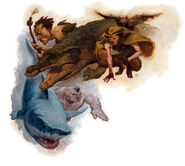

Werecrocodiles, also known as Sebek-spawn, were lycanthropes whose animal form was that of a massive crocodile.[7][9] Werecrocodiles might also assume a hybrid form with the head of a crocodile and the body of a muscular human. They were powerful hunters and were feared throughout many lands.[10]

Description[]

In their humanoid forms, werecrocodiles were biologically indistinguishable from non-lycanthropes.[7] Typically, they were humans of Mulhorandi or Chessentan ethnicity, and were tall and thin[7]—although well-muscled—typically with little body hair and bowed legs.[11] A werecrocodile's humanoid face was thin, with sharp features, a long nose and chin, a noticeable overbite,[2][7] and eyes that held a steady stare which could be somewhat unnerving.[11]

In crocodilian form, they had red eyes[12] and large, scaly bodies. While some werecrocodiles could only assume the forms of either a humanoid or a crocodile,[7] others could assume a hybrid form.[13][note 1] In this form, they were hulking, 7‑foot (2.1‑meter) tall crocodiles that stood upright on short legs.[11] Young werecrocodiles only gained the ability to shapeshift once they reached puberty.[2][7]

Combat[]

In human form, werecrocodiles were considerably strong[7] and often wielded a khopesh sword, war pick, or light crossbow.[10][13] In crocodile and hybrid forms, they relied on their sharp teeth, powerful jaws, and lashing tails as weapons.[10][7][13] In crocodile form, they only used their tails when surrounded by multiple enemies,[14] and preferred to grab single opponents in their jaws and hold them underwater.[10][7] In hybrid form, they relied much more on their tails, preferring to bite only when moving in to grapple with an enemy.[14]

Werecrocodiles liked to ambush their prey, either by getting close in their humanoid form or by lying in wait submerged under water.[2] They often toyed with their opponents' sympathies in order to lower their guard, such as by pretending to be weak or grief-stricken.[7] Werecrocodile spellcasters had even developed a spell known as crocodile tears designed to heighten the illusion of weakness or distress.[15] A favorite maneuver was to get close to a target while in humanoid form, use their great strength to grab them and drag them into the water, and then change form to hold and drown the victim.[7] They could not breathe underwater, but could hold their breath for considerably longer than most normal humanoids.[13]

Some werecrocodiles were also able to recruit or summon a small number of mundane crocodiles which would obediently aid them in battle.[7] Arcane spellcasting was rare but not unheard of.[16]

Werecrocodiles could regenerate and heal from injuries, although this process was disrupted if they were hit by a weapon made of silver.[1] They were, in general, more vulnerable to silver weapons,[10] even finding it unpleasant merely to touch the metal.[16] It was claimed by some that the same was true for weapons made of flint, and that mandrake was poisonous to them.[17]

Ecology[]

Werecrocodiles lived near water, and were expert swimmers and highly adept at using the water for cover and stealth.[13] They preferred to live in or near rivers,[14] swamps, or flooded plains,[10] and were most commonly found in the Adder Swamp,[18] the Great Swamp of Rethild,[19] the Lake of Salt,[20] and the River of Swords.[21] While they generally avoided areas with large humanoid populations,[7] some werecrocodile families were known to take up residence in the sewers of large cities, such as Skuld[22] or Soorenar.[23]

Like true crocodiles, werecrocodiles consumed anything that they could catch, including mostly fish and mammals who lived near their homes.[7] It was estimated that they needed to eat approximately 50 pounds (23 kilograms) of meat per day,[24] and their two favorite foods were the flesh of humans and the flesh of wererats.[7] They had a particular taste for human flesh,[10] and found its allure difficult to resist. They had no natural predators.[7]

Werecrocodiles were known to be carriers of lockjaw, and could spread the disease to anyone they bit in their crocodile or hybrid forms. They themselves were immune to it.[1]

Reproduction[]

As a rule, werecrocodiles only mated amongst each other, and birthed live young lycanthropes.[7] Alternatively, anyone bitten by a werecrocodile ran the risk of contracting their form of lycanthropy and transforming into a werecrocodile at the next full moon. The more grievous the bite, the more likely the victim was to contract the condition.[7]

Society[]

While they were known in rare cases to gather in large settlements,[18][21] werecrocodiles generally lived in small family colonies of up to 3 or 4 individuals, or else they lived alone.[7][13] A family was usually led by their mother[7] and sometimes kept several crocodiles as pets.[13] Those werecrocodiles who lived near rivers or swamps made their homes in crude mud huts and had few possessions or treasures[7]–perhaps no more than they could fit into a water-tight bladder to keep them dry.[12] They would spend most of their day hunting in crocodile form, then return home and assume human form to sleep during the night.[7]

Werecrocodiles had no particular enmity for humans, they simply found their flesh too tasty to resist, and were also very territorial. At the same time, they were aware that humans had the greatest potential to harm them, and they consequently tempered their hunting and territoriality with caution. Werecrocodiles avoided conflict with large groups of humans, instead picking off lone individuals or small bands that they felt confident of overpowering. They would often lure their victims into traps or disguise themselves as humans in states of intense feigned grief in order to get the advantage in their ambush.[7]

Language[]

They could be very direct and concise when they spoke, occasionally snapping their jaws and speaking with hisses or bestial tones when emotional.[12] They generally knew Common and traditionally also spoke the Mulhorandi language.[7] Out in the swamplands, they sometimes relied on short, shrill vocalizations to call out to one another.[12] Werecrocodiles could also communicate with mundane crocodiles[7] and giant crocodiles.[13]

Religion[]

Their patron god was Sebek, the crocodile-headed minor Mulhorandi deity,[7][21] and all werecrocodiles were said to be his servants.[25] Their religion demanded that they ruthlessly protect their territory and impose themselves on those weaker than them, all the while devoting their glories to Sebek.[26]

Some werecrocodiles served Sebek as clerics,[6][7] and in fact, Sebek's clergy consisted solely of werecrocodiles, notably the specialty priests called Swamplords.[25] These clerics often adapted their spells to be more crocodilian in nature, such as summoning only crocodiles when casting animal horde or using a variant of sticks to snakes that was uncreatively known as sticks to crocodiles.[27] Werecrocodile priests were known to bully other werecrocodiles, and were at the forefront of most schemes against humans.[25]

History[]

Werecrocodiles originated in the land of Mulhorand, where they were created as servitors by Sebek and served in that role for an unknown period of time.[2][7] They eventually came to be quite numerous in Sekras, a city on the River of Swords that was the center of Sebek's worship.[21] Their presence prompted paladins in service to the God-Kings Osiris and Horus-Re—who would come to be known as the Brotherhood of Those Who Smile in the Face of Death[28]—to destroy the city in the Year of the Grisly Ghosts, 1183 DR.[21][29] The paladins were said to have slaughtered even the youngling werecrocodiles, and as a result, the survivors fled[12] either south to Okoth[20] or west to the coast and on to Chessenta, where they became entrenched in the Adder Swamp.[2][7] While some continued to dwell in the ruins of Sekras, which eventually became a breeding ground for them,[21][30] there were more werecrocodiles in Chessenta than in Mulhorand by the mid-to-late 14th century DR.[2] By this time, they had established the City of the Werecrocodiles deep within the Adder Swamp,[18][27] making use of their god's power and several potent magic items which had been brought with them from Mulhorand.[16] From this city, they nominally claimed dominion over the whole Bay of Chessenta.[27]

In the Year of the Prince, 1357 DR, a family of werecrocodiles took up residence in the sewers of Soorenar and preyed on poor tradesfolk and peasants, trusting that the city's ruling nobility would not even notice the disappearances.[23]

As of the late 15th century DR, the werecrocodiles in Chessenta's Adder Swamp had established Sebakar, a nation over which they ruled like nobles.[31]

Appendix[]

Notes[]

- ↑ In Advanced Dungeons & Dragons and in the 3rd edition sourcebook Monsters of Faerun, werecrocodiles only possessed human and crocodile forms; they did not gain a hybrid form until the 3.5 edition sourcebook Lost Empires of Faerûn.

Appearances[]

- Novels

- Maiden of Pain

Gallery[]

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Brian R. James (May 2010). “Backdrop: Chessenta”. In Chris Youngs ed. Dungeon #178 (Wizards of the Coast) (178)., p. 76.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 James Wyatt, Rob Heinsoo (February 2001). Monster Compendium: Monsters of Faerûn. Edited by Duane Maxwell. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 92. ISBN 0-7869-1832-2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Skip Williams, Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook (July 2003). Monster Manual v.3.5. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 175–178. ISBN 0-7869-2893-X.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Reynolds, Forbeck, Jacobs, Boyd (March 2003). Races of Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 145–146. ISBN 0-7869-2875-1.

- ↑ Richard Baker and James Wyatt (2004-03-13). Monster Update (Zipped PDF). Web Enhancement for Player's Guide to Faerûn. Wizards of the Coast. p. 6. Archived from the original on 2016-11-01. Retrieved on 2018-09-10.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 James Wyatt, Rob Heinsoo (February 2001). Monster Compendium: Monsters of Faerûn. Edited by Duane Maxwell. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 91. ISBN 0-7869-1832-2.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 7.25 7.26 7.27 7.28 7.29 7.30 7.31 Scott Bennie (February 1990). Old Empires. Edited by Mike Breault. (TSR, Inc.), p. 92. ISBN 978-0880388214.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jon Pickens ed. (November 1996). Monstrous Compendium Annual Volume Three. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 75. ISBN 0786904496.

- ↑ Reynolds, Forbeck, Jacobs, Boyd (March 2003). Races of Faerûn. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 143. ISBN 0-7869-2875-1.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Brian R. James (May 2010). “Backdrop: Chessenta”. In Chris Youngs ed. Dungeon #178 (Wizards of the Coast) (178)., pp. 68–77.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Jennifer Clarke-Wilkes, Bruce R. Cordell and JD Wiker (March 2005). Sandstorm. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 167. ISBN 0-7869-3655-X.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Brian R. James, Ed Greenwood (September 2007). The Grand History of the Realms. Edited by Kim Mohan, Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7869-4731-7.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Richard Baker, Ed Bonny, Travis Stout (February 2005). Lost Empires of Faerûn. Edited by Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 181. ISBN 0-7869-3654-1.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Jennifer Clarke-Wilkes, Bruce R. Cordell and JD Wiker (March 2005). Sandstorm. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 168. ISBN 0-7869-3655-X.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (September 1997). Powers & Pantheons. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 126. ISBN 978-0786906574.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Kameron M. Franklin (June 2005). Maiden of Pain. (Wizards of the Coast). ISBN 0-7869-3764-5.

- ↑ Nigel Findley (1993). Van Richten's Guide to Werebeasts. Edited by Andria Hayday. (TSR, Inc.), p. 26. ISBN 1-56076-633-6.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Ed Greenwood, Sean K. Reynolds, Skip Williams, Rob Heinsoo (June 2001). Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting 3rd edition. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 183. ISBN 0-7869-1836-5.

- ↑ Thomas Reid (October 2004). Shining South. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 88. ISBN 0-7869-3492-1.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ed Greenwood, Eric L. Boyd, Darrin Drader (July 2004). Serpent Kingdoms. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 114. ISBN 0-7869-3277-5.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Scott Bennie (February 1990). Old Empires. Edited by Mike Breault. (TSR, Inc.), p. 14. ISBN 978-0880388214.

- ↑ Scott Bennie (February 1990). Old Empires. Edited by Mike Breault. (TSR, Inc.), p. 17. ISBN 978-0880388214.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Scott Bennie (February 1990). Old Empires. Edited by Mike Breault. (TSR, Inc.), p. 60. ISBN 978-0880388214.

- ↑ Nigel Findley (1993). Van Richten's Guide to Werebeasts. Edited by Andria Hayday. (TSR, Inc.), p. 35. ISBN 1-56076-633-6.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Eric L. Boyd (September 1997). Powers & Pantheons. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 125. ISBN 978-0786906574.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd, Erik Mona (May 2002). Faiths and Pantheons. Edited by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 146. ISBN 0-7869-2759-3.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Eric L. Boyd (June 1995). “Forgotten Deities: Sebek”. In Duane Maxwell ed. Polyhedron #108 (TSR, Inc.), p. 4.

- ↑ Eric L. Boyd (September 1997). Powers & Pantheons. Edited by Julia Martin. (TSR, Inc.), p. 122. ISBN 978-0786906574.

- ↑ Scott Bennie (February 1990). Old Empires. Edited by Mike Breault. (TSR, Inc.), p. 6. ISBN 978-0880388214.

- ↑ Richard Baker, Ed Bonny, Travis Stout (February 2005). Lost Empires of Faerûn. Edited by Penny Williams. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 67. ISBN 0-7869-3654-1.

- ↑ Brian R. James (May 2010). “Backdrop: Chessenta”. In Chris Youngs ed. Dungeon #178 (Wizards of the Coast) (178)., p. 72.

Connections[]

Related Creatures

Aranea • Coyotlwere • Hengeyokai • Jackalwere • Quasilycanthrope • Selkie • Shifter • Wolfwere